Last week, as a boat transporting 400 migrants drifted without fuel along a perilous migration route in the central Mediterranean, Italian authorities led a major rescue operation after Maltese authorities reportedly refused to retrieve the migrants.

Passengers’ desperate pleas for assistance went unanswered for nearly a week before they eventually reached Italian shores on Wednesday, along with 800 migrants stranded on another vessel for more than 10 days.

According to witnesses, after climbing ashore, many migrants collapsed to the ground, severely dehydrated and covered in vomit from the rough seas. Few individuals wore life vests.

Non-governmental organisations (NGOs) operating in the region, including the German organisation Sea-Watch International, reported that they had repeatedly alerted Maltese authorities to the vessel, only to be ignored.

“Malta would rather take the enormous risk of 400 people dying than provide care for them,” stated Sea-Watch.

According to the Malta Independent, the Armed Forces of Malta (AFM) informed local media that no rescue was requested by the ship’s passengers. CNN did not receive a response to its request for comment.

Critics argue that the EU’s inability to negotiate who should house a surge in migrant arrivals is causing more suffering and calamity.

When the occupants of the first two boats eventually reached safety, two more boats, each carrying approximately 450 people, were spotted at sea. CNN was informed that Sea-Watch International alerted both Italian and Maltese authorities, but neither country promptly launched a rescue operation.

Due to conflict, global inequality, and the climate crisis, the number of undocumented individuals arriving on European shores by sea has skyrocketed this year.

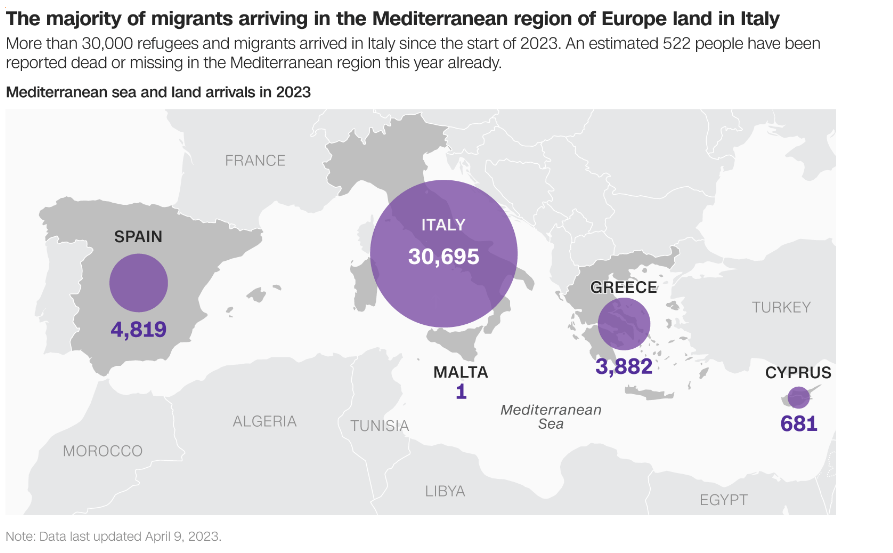

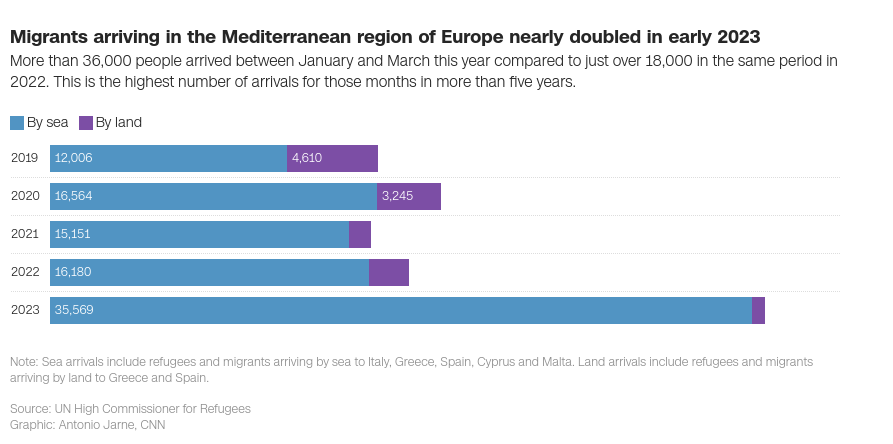

According to the most recent data from the United Nations’ refugee agency (UNHCR), more than 36,000 migrants arrived in the Mediterranean region of Europe between January and March of this year, nearly twice as many as in the same period in 2022. It is the highest figure since the refugee crisis peaked in 2015 and continued into the first months of 2016, when the arrival of over one million migrants on Europe’s shores caused EU solidarity to disintegrate into bickering and border chaos.

According to the United Nations, so far this year, more than 98% of refugees have arrived by sea, while only 2% have arrived by land. This is the highest proportion since 2016 and represents the vast majority of refugees. And an estimated 522 migrants have perished or disappeared en route, according to UN data, highlighting the lack of safe and legal routes available to refugees and asylum-seekers.

Jenny Phillimore, a professor of migration and superdiversity at the University of Birmingham in central England, stated, “People flee because they need to escape these extremely difficult situations at home.”

“Why do they take these risks by boarding the boats? Because there are no legal and secure routes, they are helpless.”

Lack of collaboration

Each year, tens of thousands of migrants fleeing war, persecution, and poverty take perilous routes to Europe in quest of safety and better economic opportunities.

However, the lack of legal and safe migration corridors for refugees and asylum seekers can have fatal consequences.

At least 28 migrants perished in March after their boats sank off the coast of Tunisia while attempting to traverse the Mediterranean to Italy. A wooden boat transporting migrants from Turkey crashed into rocks off the coast of Calabria in southern Italy a month prior, killing at least 93 people.

In December, four people perished when a small boat assumed to be carrying migrants capsized in the English Channel, one of the world’s busiest shipping lanes.

In many cases, migrant vessels are overcrowded and ill-equipped for the voyage, and the need to expend resources to rescue those on board can result in European countries shifting responsibility because authorities “don’t want people landing on their shores,” according to Phillimore.

“Italy has long been one of the countries with the highest proportion of migrants crossing the Mediterranean compared to northern European nations. “Despite the EU Commission’s efforts to promote sharing and quotas, it has not worked out,” she said.

Tuesday, Italy’s cabinet declared a state of emergency in response to the arrival of migrant boats. Even if they originate from countries that qualify for asylum status, those on the vessels are considered migrants. Until the protracted process is completed, they are not recognised as refugees.

This month, Italy’s populist, right-wing Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni will introduce new legislation that will include forced repatriation for migrants who do not satisfy the requirements for refugee status. Currently, migrants who do not meet these standards are given a notice to leave the country, but expulsion is rarely enforced unless they are stopped by law enforcement.

Given strong support from opposition legislators and the European Union, as well as Meloni’s large majority in parliament, the amendments are likely to pass. Italy has requested assistance from its EU partners in the repatriation and processing of migrants, as well as the harbouring of those who qualify for refugee status under UNHCR protocols.

“Not carrying their own weight”

Elsewhere in Europe, humanitarian organisations have criticised leaders for proposing policies to restrict border access in order to alleviate pressure on wealthy nations, whose systems for dealing with undocumented migrants are overburdened.

Recently, opposition legislators and human rights activists criticised the British government for its “cruel” and impractical plans to house migrants in decommissioned military bases and barges instead of hotels.

It occurred as the cabinet of British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak was accused of violating international law by proposing an illegal migration bill that would send refugees and asylum seekers who arrive in the United Kingdom by boat to Rwanda or their country of origin.

According to the UK government, 74,751 asylum requests were lodged in the United Kingdom in 2022. According to the Home Office, the number of individuals awaiting an asylum decision more than doubled between 2020 and 2022, from approximately 70,000 to 166,300. The British immigration system, according to critics, has been neglected and is deteriorating.

Adam Wagner, a leading human rights barrister, told CNN in March that the bill would prevent a large group of extremely vulnerable refugees from relying on human rights protections by leaving it up to the Home Secretary to decide who should be protected and who should be deported and excluding the courts almost entirely.

According to the Italian Ministry of the Interior, 77,195 people requested asylum in Italy in 2016. Of those, 52,625 asylum applications were reviewed, and 53 percent were denied. Those who are denied can file an appeal, but the majority flee and remain undocumented.

According to the French Interior Ministry, of the 137,046 asylum requests registered in western France in 2022, 56,179 were granted. In 2022, the Federal Office for Migration and Refugees of Germany reported that 244,132 asylum applications were lodged. Some of the authorised applications included requests from the previous year that had accumulated due to a backlog.

According to the European Union Agency for Asylum, 37,300 asylum applications were filed in Greece in 2022, a third more than in 2021. 30,886 were examined, of which 19,243 were approved and 11,646 were denied.

A month earlier, the UNHCR condemned allegations that nearly 100 migrants were stripped of their clothing at the Greek-Turkish border. Greece completed construction of a 40-kilometer (25-mile) wall along its border with Turkey in 2021 out of concern that the Taliban’s seizure of Afghanistan could result in an influx of asylum-seekers.

Greece was the epicentre of Europe’s migrant crisis during the middle of the 2010s, when millions of refugees and migrants from Syria, Afghanistan, and Iraq traversed the continent. Since then, it has adopted a hardline posture, rejecting requests from Turkey and international organisations to permit more migrants to cross its borders.

“The solution to this problem is not limited to the response of a single country; the countries that have fueled geopolitical inequalities and caused the sort of problems that people are fleeing… Furthermore, the Global North is not carrying its weight, as stated by Phillimore.

“(Countries in) the Global North have more money, but they are taking in far fewer people.”

“Retaining human life”

According to researchers, the inability of European leaders to coordinate a cohesive response to increased migrant arrivals and relocate asylum-seekers across the continent has created a “political deadlock.”

During the 2015 migrant crisis, a convergence of political conflicts, including the rise of ISIS, the Syrian civil war, and instability in Afghanistan in the Middle East and elsewhere, prompted a record number of individuals to abandon their homes and attempt to reach Europe.

According to UNHCR, approximately 4,000 people are believed to have perished while attempting to reach Europe via the Mediterranean in 2015.

The majority of refugees entering the EU travelled through Libya. Luca Barana, a research fellow at Istituto Affari Internazionali (IAI) and Coordinator of the T20 Italy Task Force on Migration, stated that at the time, the EU had entered a new agreement in the Mediterranean founded on “cooperation with Libyan authorities.”

In the wake of the Libyan civil war, Tunisia has become the new gateway to Europe, but while there is an agreement between Italy and Tunisia, there is no EU-wide agreement of a similar nature. Barana added that the departures from Tunisia have increased due to “increasing hostility and discrimination against Sub-Saharan migrants residing in Tunisia.”

Barana noted that rather than employing a “cooperative” approach with Tunisia, the European Union is investing in improving border control infrastructure and increasing the number of returns and readmissions.

Human Rights Watch (HRW) deemed it “deeply alarming” that EU nations are attempting to rescind on their commitments to rescue refugees and asylum-seekers adrift at sea.

A spokesperson for the international NGO told CNN, “As more people are forced by conflict and human rights violations to undertake dangerous journeys across the Mediterranean to seek safety in Europe, it is deeply alarming and disappointing that EU countries are attempting to abdicate their responsibilities under international law to rescue people in distress at sea.”

Liz Throssell, a UN spokesperson for human rights, has also demanded an end to policies that facilitate human rights violations against migrants. “UN Human Rights has also repeatedly condemned the prevention or obstruction of humanitarian search and rescue efforts, including the impounding of vessels and the criminalization of aid providers and other defenders of migrant rights.”

After attempting to rescue stranded migrant boats at sea, a number of NGO employees confronted legal obstacles. In January, human rights organisations and the European Parliament condemned vehemently the trial of 24 emergency workers in Greece, who were arrested in 2018 for assisting refugees whose dinghy became stuck after departing Turkey.

Daniele Fiorentino, a professor of political science at Roma Tre University in Rome, Italy, stated that the EU’s policies regarding migrant boat arrivals in the region should prioritise refugees whose lives are in danger.

CNN quoted him as saying, “Perhaps the situation is less dire today than it was in 2015, but the tragedy… is the result of a weakness or inefficiency in the decision-making process in both Italy and Europe.”

Who is responsible for rescuing individuals lost at sea, who oversees the process, and who makes the decisions? In doing so, authorities and all of us should never lose sight of the fact that saving lives is the most pressing issue at hand.